Building up from the Back - Motta’s Bologna Recipe for Success

The Italian side is currently fighting for Champions League qualification. In this article, we look at how Thiago Motta made the build-up from the back a strength without a proper playmaker on the pitch.

There are many cliches in Serie A, and some of them lean into the idea that it’s a conservative league, where all managers don’t like to take risks and games just pass by at a slow pace. Even if some of these misconceptions aren’t too far from the truth, there are actually some instances when Italian football, in the last few years, has actually been a trailblazer. As an example, nobody liked to experiment with new solutions to build up from the back more than Serie A did.

There are many teams that, step by step, have found new ways to develop the first build-up, turning it to their advantage. First, it was Maurizio Sarri’s Napoli that showed how to lure the opponent pressure with short distances and the passing game. Then, it was De Zerbi’s Sassuolo that made the very same idea the cornerstone of their football. At the same time, Antonio Conte’s Inter was leveraging the quality of their defenders and Brozovic to become a team impossible to put pressure on.

And we are now at the last frontier of the experimentation with the low build-up in Italy with Simone Inzaghi’s Inter, a team that takes advantage of the build-up from the back to attack while running and that has completely dissolved the concept of positions.

All the aforementioned cases have a common denominator. Other than the brilliance of their collective systems, each of these teams partially leaned on the playmaker’s ability to receive passes from the defenders and dictate the tempo: Jorginho and his first touches at Napoli, Locatelli at Sassuolo, Brozovic and his ability under pressure both under Conte and Inzaghi, and finally Çalhanoglu with his atypical interpretation of the role.

Alongside this year’s extraordinary Inter, though, there is another Serie A team that is building its fortunes from a meticulous build-up from the back: Thiago Motta’s Bologna.

The main difference between the Rossoblù and the other excellence of Italian football is the absence of a proper playmaker. If you notice, when we talk about Bologna we praise Zirkzee’s technique, the eclecticism of the inside forwards, or Orsolini’s verticality. But no deus ex machina coordinates his teammates on their own, with their skills, carrying the ball out from the back. The absence of a playmaker then becomes yet another sign of Motta Bologna’s fluidity, as he was able to set up an effective low build-up by using space manipulation, counter-balancing a midfield that surely doesn’t shine for technical skills.

It's a way to stamp his mark on the team that Thiago Motta also used to embrace the management’s decisions in the transfer market. For a few years now, Bologna have been signing players with great physique and intensity in midfield, without any proper playmaker.

In the theoretical role of deep-lying midfielder in Bologna’s 4-3-3 in recent weeks, we saw an alternation between Freuler and El Azzouzi, not the most technical midfielders in the league. Nevertheless, the Rossoblù always managed to build up from the back seamlessly.

Two of their recent games are particularly interesting to see the way in which Bologna move. The two opponents were Fiorentina and Lazio, two teams that have opposite attitudes when not in possession: extremely aggressive and man-oriented for Italiano’s side, more cautious and ball and structure-oriented for the Biancocelesti.

A Peculiar Way to Use Defenders

Like many other teams that try to find edges through the build-up, Bologna occupy space with the objective of stretching out opponents on the pitch. The players that are involved in the first possession are usually the defenders and deep-lying midfielders, organized – depending on the situation - in a 4+1 or 3+2 shape.

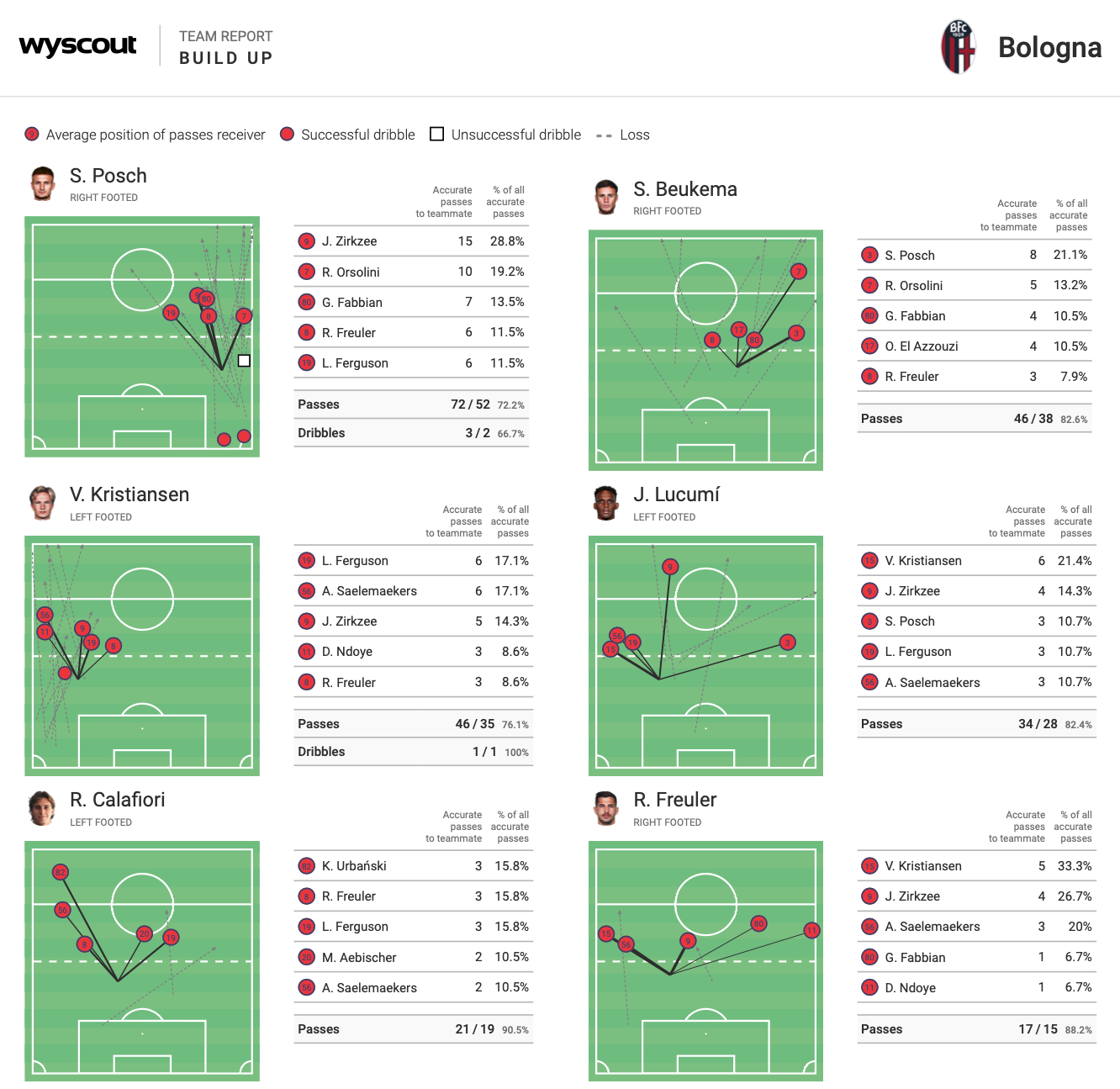

If in the opposing third, it is clear how superior Zirkzee’s technique is in comparison to his teammates and, among the players that are involved in building up from the back, there’s not only a lack of a proper playmaker but also of players that are above average from a technical standpoint: no playmaking full-backs, no hyper-technical center-backs. Everyone, on their own, has good confidence with the ball at their feet and this is enough in a system in which the ability to recognize spaces tells the players what to do when in possession, with no need to come up with creative ideas.

It can be noted in the shifts from the 4+1 shape to the 3+2 one: to take the midfielder position alongside Freuler or El Azzouzi, it can be either the center-back or the full-back. It’s mostly Calafiori among the center-backs but that kind of movement has been a constant even for Lucumi against Lazio and Beukema against Fiorentina, two games when Calafiori was subbed in and only played a few minutes.

The center-backs can become midfielders either in a static manner – by occupying that position even before the goal kick - or naturally by following the development of the play. The players rotate and the center-backs recognize the moment when they need to move forward because the space is free. Otherwise, the center-back carries the ball forward for a few meters, gets into midfield, passes the ball to a teammate, and stays in that position with Freuler or El Azzouzi.

Whether it is Beukema, Lucumi, or Calafiori, these Rossoblù defenders all learned how to stay in midfield, particularly playing with the goal to their backs: the most uncomfortable situation of all, even more so for a central defender. Lucumi and Calafiori are particularly good at first-touch passes – a must-have to survive in that position – but are also very good at orientating control to avoid pressure.

This way of using defenders had an immediate impact against Fiorentina. Beukema or Lucumi’s progressions were used to misdirect Fiorentina’s man-marking and, most of all, to free passing lanes for Zirkzee to link up play. One of the two center-backs moved forward to become a midfielder and then shifted laterally during possession, carrying the opposing striker who had to mark him. By doing that, a passing lane opens for Zirzkee, allowing him to link up with the wingers or inside forwards. The fact of moving a defender forward alongside Freuler allowed Bologna to keep the inside forwards Ferguson and Aebischer high up the pitch, making their life easier in leading offensive plays when Bologna was able to switch sides with the build-up.

Every time Motta’s side were able to overcome Fiorentina’s pressure, the players touched the ball only a few times, often playing with first touches: they didn’t need the skills of a valid playmaker under pressure. Because of his nature and the necessity to always play with his back to the goal, Zirkzee was the only one allowed to touch the ball more times during the build-up.

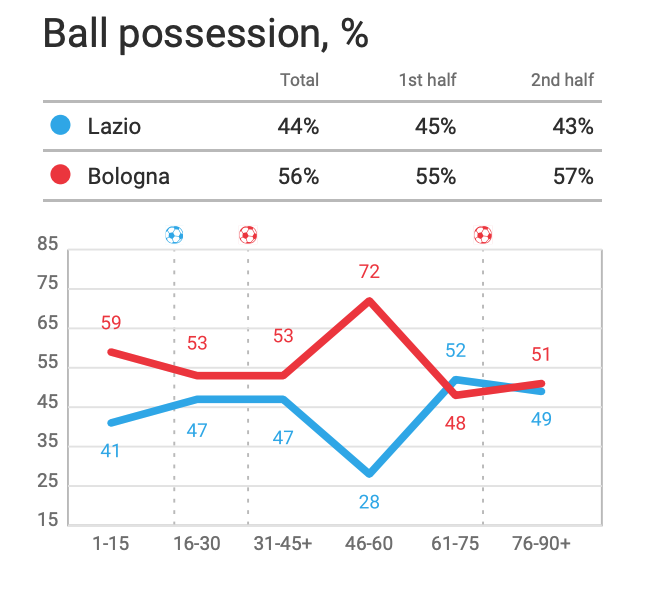

If the game against Fiorentina represented some sort of “extreme” example because of the opponent’s attitude, the win at home against Lazio proved how Bologna can use the build-up from the back even for less obvious advantages. Possession at the back was useful to change the game's momentum in the second half and to control it, creating the premises for Zirkzee’s goal.

Lazio don’t love to risk too much with pressure and they’re a team that is always trying to find a middle ground between their will to be aggressive and maintain compact lines, two variables that are harder and harder to marry together simultaneously in modern football.

Bologna only needed to find a way to get the ball to the wingers, or to the men placed behind Lazio midfield’s lines. The Biancocelesti beyond the line of the ball would have to run back quickly to double-team, leaving space for Motta’s boys to pass back to the defenders or deep-lying midfielders: an “innocent” passing option on paper, that nonetheless gave Bologna control of possession for large chunks of the second half. As a response, Lazio could only move back.

By doing this, Bologna were able to move the ball forward with calm and compactness: Lazio never had the chance to counter-attack because such a tidy possession favored the Rossoblù’s gegenpressing. As an example, after an unsuccessful cross they were immediately able to run forward to win the ball back in the opposing third.

It’s quite hard to find teams that have such a deep and varied level of organization. Thiago Motta’s work puts the most talented players in the best scenario to play at their best, also reassuring less technical players when in possession. It turns out that Inter is not the only team in Serie A in which it’s really hard to distinguish positions on the pitch.